In 1838, a 28-year-old Abraham Lincoln stood on the stage of the Young Men's Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois, and spoke out against slavery. Lincoln -- till then mostly unknown -- believed that slavery would corrupt the federal government, and that the mob violence committed against abolitionist movements in the United States represented a threat to the country as a whole. In his most famous line, he declared that the destruction of the US could only come from within.

"At what point shall we expect the approach of danger? By what means shall we fortify against it? Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant to step the ocean and crush us at a blow? Never! All the armies of Europe, Asia, and Africa combined, with all the treasure of the earth (our own excepted) in their military chest, with a Bonaparte for a commander, could not by force take a drink from the Ohio or make a track on the Blue Ridge in a trial of a thousand years. At what point then is the approach of danger to be expected? I answer. If it ever reach us it must spring up amongst us; it cannot come from abroad. If destruction be our lot we must ourselves be its author and finisher. As a nation of freemen we must live through all time or die by suicide."

The speech helped cement Lincoln's reputation as a speaker, and his stance as an abolitionist. But — it needs to be said — his timeline is a bit immodest.

“Live through all time”? Even the Nazis limited their Reich to a thousand years.

Regardless, America, at the moment, seems to have chosen Lincoln’s latter option. America — with a departing Nazi President and an ascendant Nazi movement, with an impotent liberal establishment and an immensely powerful billionaire kleptocracy, with a tanking pandemic-stricken economy, with $1.6 trillion in student loan debt, with the looming chaos of catastrophic climate change — feels tenuous in a way that it did not a mere 30 years ago, when I was a kid and our establishment was proclaiming that the end of the Cold War meant “the end of history.”

America, at least as we know it, may not be long for this earth.

No civilization lasts forever

Pick a place on earth and watch the course of its human population over time. Let's pick China. There has been some sort of Empire in China for probably 42 centuries. But if you look at a timelapse of those dynasties you'll see an empire whose land is constantly expanding and contracting, breaking into pieces and then reuniting. With a deep Imperial inhale, the borders slip over into Tibet, out into Mongolia, and then with the exhale they shrink back to well within the current borders.

Within those breaths, too, are entire revolutions, massive transformations of the social order, when entire cities, ethnic groups, and local histories were burnt to the ground. We think of China as this ancient civilization, but in reality, the current nation of China has existed since the establishment of the People's Republic in 1949. All of my grandparents are older than China.

Even our borders in the US are not the solid block we imagine. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were only 45 states. The last two, Alaska and Hawaii, weren't annexed until 1959. The US, as it currently exists geographically, is only 61 years old, and even that's only if you don't count the quasi-conquered lands that we added and lost in the Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan Wars; that's only if you leave out the proxy governments installed in the Middle East and Central America, our little capitalist Vichy outposts. If you looked at a timelapse of the expansion of the US globally over the past couple centuries, there would have been massive additions early on, but now, it would have slowed, and you may start to think that this was the crest of the breath, that the exhale was now inevitable.

Yes, you may say, but the government as it currently exists has been around for 244 years. That's something, isn’t it?

Is it? Universal women's suffrage has just hit its hundredth birthday in the United States. And universal male suffrage, while nominally the law since the end of the Civil War, was not true in effect for Black Americans in the South until the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. 56 years ago. If you're a Millennial, your parents are probably older than American democracy.

We don't allow ourselves to think these thoughts because the United States feels like the ground underneath us. We wave its flags, we sing its songs, we even fight and die in its wars. To question the permanence of the United States is, for many of us, to question our very identities.

The United States has existed for about 12 generations. Do you really think it will still be here, in this current form, in another 12?

How civilizations fall apart

In 2005, the American anthropologist Jared Diamond published the book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed. In it, he compared several major human civilizations that have collapsed over time, and found that there were five possible factors that could lead to collapse.

Climate change

Hostile neighbors

Collapse of essential trade

Environmental problems (soil depletion, introduction of non-native species, overpopulation, etc.)

The society's response to one or all of these four pressures.

Diamond, an optimist, believed that a smart, adaptable society could survive these pressures if it took decisive action, but if a society blundered or dithered in response, it would eventually collapse.

Collapse, for Diamond, was defined as "a drastic decrease in human population size and/or political/economic/social complexity, over a considerable area, for an extended time." It's an interesting definition, because the word "collapse" as we think of it in the popular consciousness takes place over the course of a day or two. We are literally thinking of the first scene of a zombie movie, where someone wakes up from a coma or after a night out and suddenly there are shambling hordes of brain-eaters charging at them down the street.

But that’s not what collapse looks like. It is not a global, sudden catastrophe. It is a progression of smaller catastrophes. Which means it happens over the course of not days, but decades and centuries. In other words, it is slow in relation to a single human life.

Ecologist and writer John Michael Greer makes this point in his book The Long Descent. Our culture, Greer says, holds two opposing myths about our future. The first is the myth of eternal progress, that we will keep innovating our way out of things and will end up living among the stars. I will admit that I personally rather like this myth, and have always felt nice warm feelings reading the works of the myth's chief proponent, Carl Sagan. But, as Greer points out, there's literally nothing that has happened historically, and certainly little happening now, to suggest that we will be the first ever civilization to not enter into decline.

The second myth about our future is the apocalypticism adopted by pessimists, religious fundamentalists and doomsday preppers. This myth, like the progress myth, is not rooted in historical reality. It is violent and dramatic, almost righteous in its totality. It is a complete collapse of the world order, a return to the Dark Ages, but more desperate and violent.

The only way this second myth would really happen, though, would be if there was a global nuclear war. But even that wouldn’t be immediate — the places not directly hit would have to wait a bit for total crop failure and the ensuing famine, for radiation sickness, for the slower growing cancers to take hold. It would be a quicker collapse than most, but it would not be immediate.

Historically, Greer says, collapses are slow. They are not global, and they are not complete. Instead, they take place as a series of crises happening in different areas over a longer period of time. These crises take many different forms. On the smallest level, they are personal. Someone who has been under enormous pressure finally has a mental health breakdown, which could take the form of addiction, acts of violence, mental illness, or even suicide. A family finally can’t pay the rent and is evicted from their home. A town can no longer afford its library, it’s after-school daycare, it’s extra-curriculars and arts programs.

As these small crises start to increase, they snowball into larger societal problems: a decline in the quality and an increase in cost of healthcare leads to higher death rates and more bankruptcies, which lead to a smaller tax base, which leads to crumbling roads, the selling off of parks and public lands, and an inability to remove old lead pipes, which in turn causes more widespread health problems. This weakening of the civilization’s core means that it is more vulnerable to the less predictable (but still inevitable) catastrophes, like earthquakes and hurricanes and floods and pandemics and terrorist attacks and economic contractions. Over time, the small catastrophes start to aggregate into very big ones.

"On average," Greer writes, "civilizations take between five hundred and one thousand years to rise out of the ruins of some past civilization, then decline and fall in their turn over a period of one to three centuries."

From a historian’s bird’s eye view, this may be “collapse,” but from an individual’s viewpoint, this would feel less like collapse and more like “descent.” In Greer’s “Long Descent” scenario, the changes would be felt on a generational level rather than instantaneously — each generation would notice that their parents had it a little better off than they did. Their education would be a little more expensive, their healthcare a little worse, their quality of life a little bit lower, and so on.

You could be forgiven for thinking that this all sounds familiar.

Imagining a time after America

Americans, at the moment, seem to imagine that they’ve dodged a bullet with the election of Joe Biden. The rhetoric of his campaign was based around restoring honor and dignity to the White House, around restoring civility to the political discourse, and around bringing us back to the golden, honorable, Obama years.

The slogan, god help us, could well have been “Make America Great Again.”

This is not meant to equate Joe Biden with Donald Trump: another four years of Donald Trump and our democracy may well have been totally over. But even though Biden will obviously be infinitely better than Trump, we aren’t going to be returning to the America of the past few decades. The damage Trump did to the system in his four years is permanent, and while some things he destroyed will be patched up and fixed, many will linger with us, much like the unoccupied “X-ed” houses that still dot New Orleans 15 years after Katrina. The far-right Supreme Court will be with us a long time. Some, but not all, of the public lands he sold off will be clawed back. And the climate? Well, we’ll never get those four years back, and they were four years we needed.

Those losses aside, the fabric that makes this country into a coherent, unified nation is fraying. Some of this is intangible: we’ve never really had a shared history or culture, because our divisions have always been endless — North vs. South, Right vs. Left, Coasts vs. Heartland, Men vs. Women, Black vs. White, Immigrant vs. Native, Colonist vs. Indigenous, Urban vs. Rural, Rich vs. Poor, etc. — but now we don’t even seem to have the core idea that made America worth it to most people, “the American Dream.” The idea that anyone can become anything here has less traction than it did a generation ago, as the Millennial Generation enters its late 30s and early 40s still saddled with debt and still without homes or secure jobs. The American Dream was always mostly bullshit — disproportionately available to straight white men, extra available to people with family money and decent connections — but enough people made good a generation ago that you could believe that work would set you free.

But mythology is only part of it. What really makes a country whole is it’s infrastructure and its institutions. It’s the fact that you can pay a few cents and have your mail delivered anywhere in the country for that one standard price. It’s that you can hop on a train or get in your car and go anywhere in the country with no barriers put in your way. It’s that you can count on clean water, on untainted food, and on basic legal protections wherever you go.

Can we really say we have that? Our Postal Service is being actively dismantled — do the men doing this know that Washington and Madison saw a Post Office as vital in pulling together the United States in its fractious early days? Our roads and bridges are crumbling, and our train system is an embarrassment. How do you feel connected to places you can’t get to? In many cities, the water is basically poison. Our agricultural system is a nightmare. And only certain people can count on the protection of the law, as the massive difference between the police responses to Black Lives Matter protests and to the white nationalist storming of the Capitol shows.

These aren’t straws we’re putting on the camel’s back, they’re anvils. It’s not sustainable. It’s too much pressure for a system to bear. It’s hard to face, but it may be that the pressures currently bearing down on the United States are not pressures it is capable of withstanding.

This sounds like pessimism, but it doesn’t have to be. Consider:

All civilizations eventually collapse.

When civilizations collapse, it typically does not involve everyone in that civilization dying with it. Like, Pompeii aside.

When the United States of America no longer exists in its current form, there will probably still be people living in the United States of America, and they could build all sorts of new, different ways of living on that land.

Now, the moment where the USA is no longer around may still be generations down the line, but it does not hurt for you to start thinking about what that future looks like. And don’t give in to pessimism — imagine something nice.

Our culture has an allergy to utopia. In an interview with The Ransom Note, cultural historian John Higgs pointed out that we've abandoned the idea of a bright future almost entirely:

"It seems to me that the last ditch attempt to say something positive about the future was in 1989 in Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, when they say ‘The future will be great – it’s a bit like now, but with really great waterslides’. That was the best they could do. Ever since then the future has been shown as environmental apocalypse, zombie films, all of these things."

For Higgs, this is worrying, because if you wish to create something -- a piece of art, a chair, a machine, a scientific theory -- you have to be able to imagine it first. All of humanity's wondrous creations have existed in the nebulous foggy realms of the human mind before they've ever existed materially in the real world, so the death of an entire culture's imagination on any one subject means that much that could've been created won't.

Our current media diet is so focused on the decay and collapse part of what’s currently going on that most of us can’t fathom solutions outside of building a bunker and surfing prepper sites. But there are realistic visions of a future utopia that are already out there, there are futures we could start working towards that aren’t just Hunger Games and 28 Days Later. I have, for those interested, a few books to check out if you are ready to think beyond the more, ah, “practical” Democratic vision of passing voter reform, the Green New Deal, Medicare For All, Immigration Reform, Marijuana Legalization, Abolishing ICE, getting a Billionaire’s Tax, and also stuffing the court in the two years between now and when the Republicans inevitably take one of the houses of Congress back.

Books about the future that won’t fill you with despair

A Paradise Built in Hell by Rebecca Solnit

A Paradise Built in Hell is a history of “disaster utopias,” which are what Solnit calls the communities that arise after a disaster occurs. She profiles five major disasters over the course of the last century and a half (from the 1906 San Francisco earthquake to Katrina), and examines how the public responds to these events. If you believe our mass culture, we turn into greedy, “every man for himself” looters who need to be put back in line by the restoration of public order.

In reality, this is a myth that is pushed by the powerful. Many studies have shown that acts of looting are almost always wildly exaggerated, and that during a disaster, most communities actually come together and take care of things before “the authorities” even arrive. After 9/11, Solnit points out, the nation rightly applauded the New York City firefighter who stormed into the building and saved lives. But very little credit goes to the people who were already in the building, who actually saved more lives than the firefighters. Nor do we hear about the 9/11 boatlift, a spontaneous evacuation in which boat owners from New Jersey and Staten Island evacuated 500,000 people (more than Dunkirk) from the toxic clouds of debris that were covering lower Manhattan that day. In almost all disasters, it is the people who are already on-site who do most of the saving, because they don’t require things like a “response time.” These rescues are self-organized, decentralized, and lacking any major authority.

If you’ve lived through a disaster, if you’ve been somewhere after a hurricane or a tornado swept through, you’ve likely experienced this. A community’s barriers and social structures break down in a disaster, and people show up to pitch in without being asked. Churches fill up with donations, mutual aid groups scramble boats to pick up people who are stranded and deliver water and phone charging stations to the thirsty and disconnected.

The violence and chaos, Solnit finds, is usually caused by the powerful who are trying to restore order, or by the people who expect looting, and get trigger happy when a neighbor shows up to offer help.

The lesson, in short: we do just fine even without our governments. People are smarter and better than we give them credit for. We can trust each other more than we imagine.

The Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler

The Parable of the Sower got a lot of press in 2016 for its prescience: it was written in 1993, and is about a 2020’s America that is plagued by economic collapse, severe climate change, drug epidemics, and a right-wing President who insists he is going to return America to it’s richer, more prosperous days.

It’s a particularly bleak dog-eat-dog dystopia, (one that A Paradise Built in Hell might suggest will not come to pass) but what’s most interesting is the religion that the young protagonist events. It is best summed up by the novels first few lines:

All that you touch you Change.

All that you Change Changes you.

God is Change.

The religion has since been made into a real-life thought system called Emergent Strategy, outlined in a book by activist and organizer adrienne maree brown. The core idea is that you don’t fight change — you move with it, and in doing so, try to shape change in a way that creates a better, more just future. If you’re looking for a belief system that can see you through a time of chaos, this is a great place to start.

Small is Beautiful by E.F. Schumacher & America Beyond Capitalism by Gar Alperovitz

As the federal government becomes less and less responsive to its constituents (who broadly want better access to healthcare and a Green New Deal and gun control), the easy thing to do is to fall into despair, to imagine that nothing will never change. This is unnecessary — people have the power to start building a better world with or without the consent powerful, and these two books outline strategies for doing so. Schumacher is famous in ecological circles for putting forward an economic theory that acts “as if people mattered,” rather than capital or economic growth. It’s a radically different vision of society, and one that we’re honestly pretty far from, but he gives some ideas for how it could work.

Alperovitz is more focused on the changes already happening in the United States, particularly with people who are experimenting with alternative ways of doing business. To use one example: a reason a lot of companies are so terrible is that they are legally required, in their corporate charters, to act in a way that maximizes profit for their shareholders. So if a CEO were to, say, decide to stop dumping chemical waste in a local river even though dumping it elsewhere would be more expensive, the shareholders could sue him for losing them money, so long as there wasn’t a regulation in place requiring that they not pollute the water.

Some companies (called “B Corporations”) came up with a workaround — they developed a different type of corporate charter which allows for the company to make decisions that are not only good for their profits, but are also good for the community they live in. It’s a subtle difference, but it’s an important one, because it means that companies don’t have to be regulated by the government to make ethical choices. On top of B Corps, Alperovitz gives dozens of other things people are doing to create a better, more just grassroots economy (from worker-owned co-ops to building local wealth to encouraging more democratic forms of banking). Both books are worth a read if you think that the ideas coming from the left are unrealistic.

The Future Starts Here by John Higgs

The Future Starts Here is a spiritual sequel to Higgs’ excellent Stranger Than We Can Imagine, which was an attempt at explaining the totally baffling 20th century. In FSH, Higgs is attempting to predict what will happen in the 21st century by looking at issues like space exploration, climate change, artificial intelligence, and social media.

The book is effectively an experiment: In a hyper-networked world where misinformation is rife and authority can’t be trusted, Higgs realizes the only thing you can trust is, well, the people you already know and trust. So his research into these topics goes almost entirely through his friends and collaborators. This experiment fails to get him any easy answers as to what the future looks like, but it’s an incredibly interesting model for how we can place ourselves in the world in this completely overwhelming century. Our networks are what will save us.

Hope in the Dark by Rebecca Solnit

Solnit’s Hope in the Dark was published after the despair she saw among her friends during George W. Bush’s re-election, and it seems to go back into print every time something terrible happens, whether it’s the global financial crisis or the election of Donald Trump. In this absolutely must-read book, she looks back at the people who have changed history in the past, from Gandhi to Martin Luther King, Jr., to Vaclav Havel, and she discovers important lessons on how to hold onto hope in situations that appear to be hopeless.

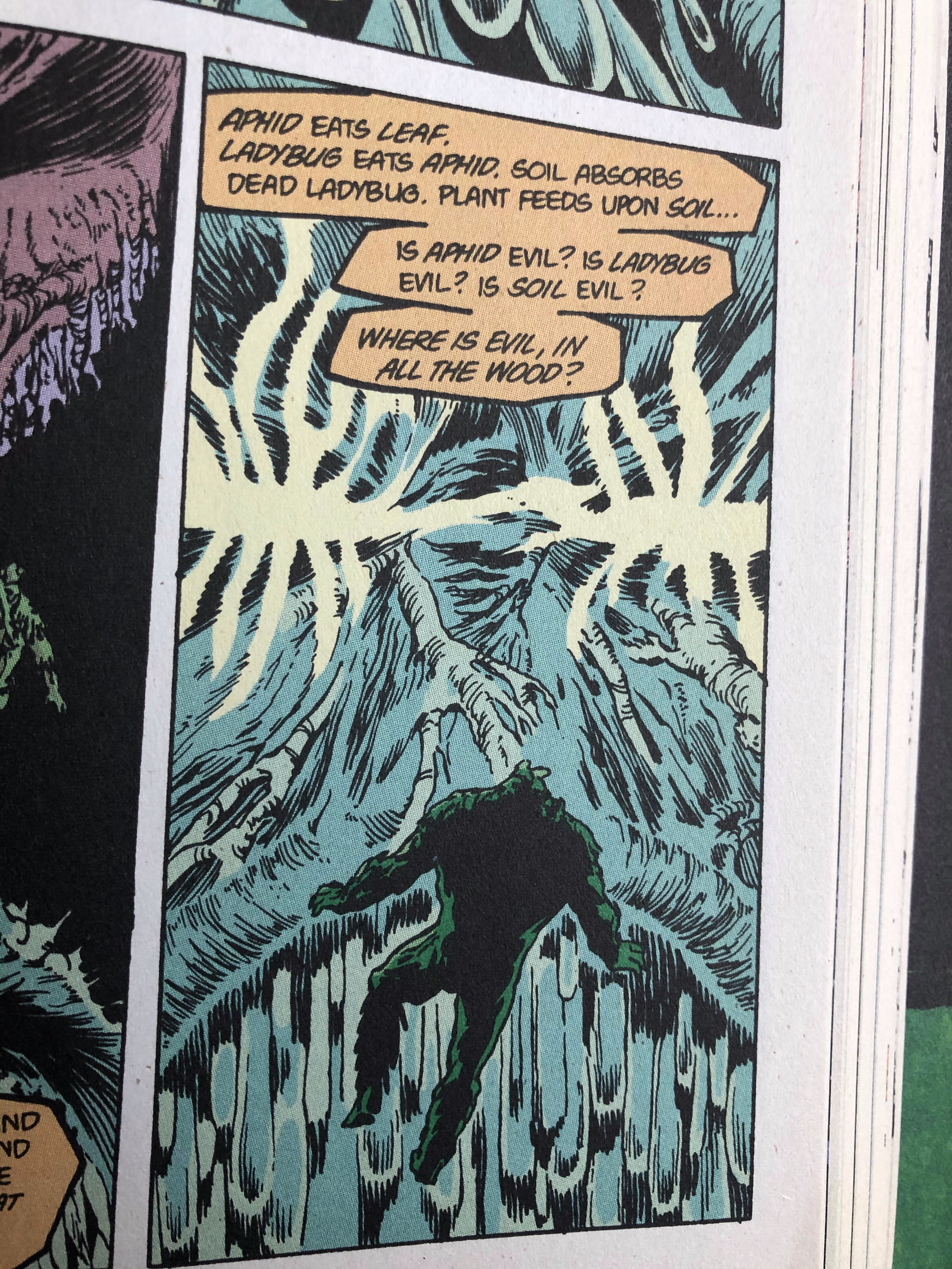

Swamp Thing by Alan Moore

Gotta throw a comic in here: Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing is about a giant humanoid plant that stalks the Louisiana bayous and occasionally fights monsters. So it’s a bit more fun than everything else on the list. But it also has a storyline that fundamentally altered my perspective on the nature of good and evil, best encapsulated in this panel, in which the hero, Swamp Thing, is talking to the elder trees of the forest:

It’s a trippy fucking comic, but sometimes what you need to get through hard times is a broader cosmic perspective. Swamp Thing (as well as Alan Moore’s magnum opus Jerusalem) have realistic perspectives on the universe that will energize you rather than deflate you.

The books mentioned in this post are affiliate linked, which means if you click the link and then buy it, it kicks back some money to me. I pick the books myself, no one’s telling me which ones to promote. The affiliate sites I use are IndieBound and Bookshop.org, both of which support local bookstores.