I started blogging during my semester abroad in 2007. I had recently dropped out of my film school program, and, high on reading Hunter S. Thompson, decided I was going to become a journalist.

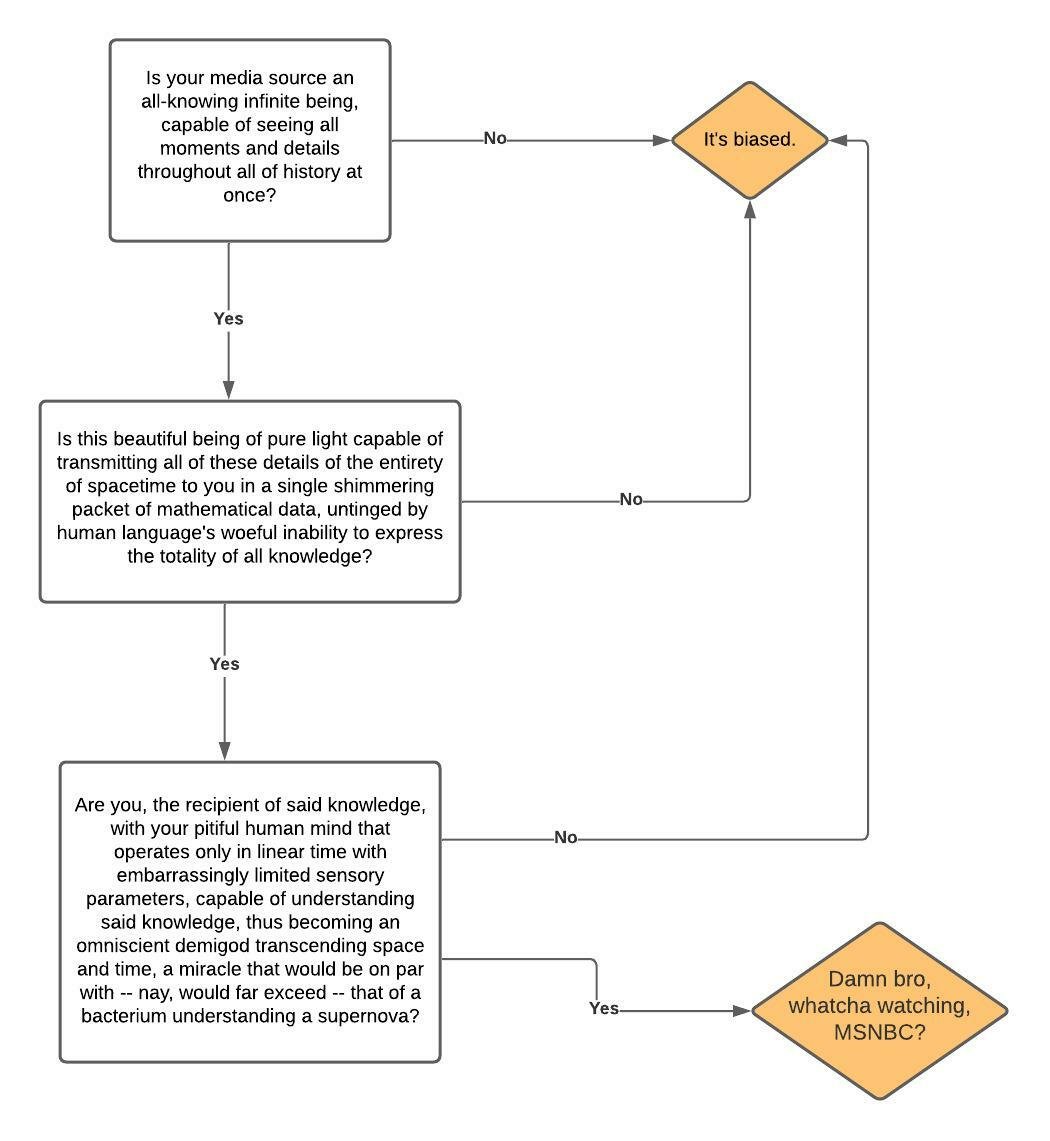

Journalism school was not, in retrospect, a good idea. My professors were teaching us how to work in a newsroom and mostly dismissed the internet as a fad, or as a place where "real journalism" didn't happen.

And then the next year, the entire industry collapsed, along with the economy. And just in time for me to graduate from college! What jobs remained were almost entirely online, and newsrooms were shuttered all around the world.

I spent the next decade trying to make it in writing. I worked for a sketchy SEO company that operated out of the offices above an abandoned arcade, I got a master's degree in human rights to supplement my knowledge base and make some connections, I worked for an immigration nonprofit in DC, and finally, in 2014, I scored a gig editing for a travel website, all while trying to figure out my "brand" and build up social media clout and pick up freelance gigs on the side.

I finally burnt out in 2018, when my daughter was born. The website I worked for was rocked by sexism complaints and was plagued by a generally toxic, Silicon Valley-style culture. I began to realize that the purpose of our writing was not to open the world up to people, but instead to write clickbait, which we could then sell to advertisers for local tourism boards (at one point, the state of Idaho's tourism board tried to get me fired for making a crack about potatoes). Travel itself, I also began to understand, was one of the primary industrial drivers of climate change and ecosystem destruction, and could not sustainably exist on the scale that it currently does. This was not an opinion one could have on a site where 100% of the revenue came from the tourism industry, and where "travel is fatal to bigotry, narrow-mindedness and blah blah blah" was a cultish mantra.

On a long drive back to my hometown with my infant daughter, my wife, who'd listened to me complain about my job for about half of the 10-hour drive, said to me, "You know, you could just… quit. Like, first thing tomorrow."

So I did. I got a job at the local library, where I buy comics and run programs and a digital literacy lab, and I've spent the past four years, in my rare moments of free time, working on a pair of books.

This has been good for me. The intervening time has made me more and more certain that the current layout of the internet, with its premiums on rapid production of "content," with its emphasis on short attention spans, and with its algorithms designed to maximize ad revenue rather than healthy debate or thought, is absolutely devastating for our collective soul.

I miss the old internet, which was so fucking weird. My friends used to send each other random shit we'd found on Stumbleupon and Tumblr, like A Story from North America, Rejected, or Wizard People, Dear Reader. Even if something felt too weird (looking at you, Salad Fingers), it was at least confirmation that I was not alone in conformist, boring Cincinnati, and that somewhere out there, there was a dope world full of dope shit.

I do not think that is the function of the internet any more. I think the rich and powerful have learned (as they generally do) how to manipulate it to their ends, which means bubbles are more likely to be solidified and fortified, while the weird quirky shit largely gets relegated to the corners.

Wondrous creatures

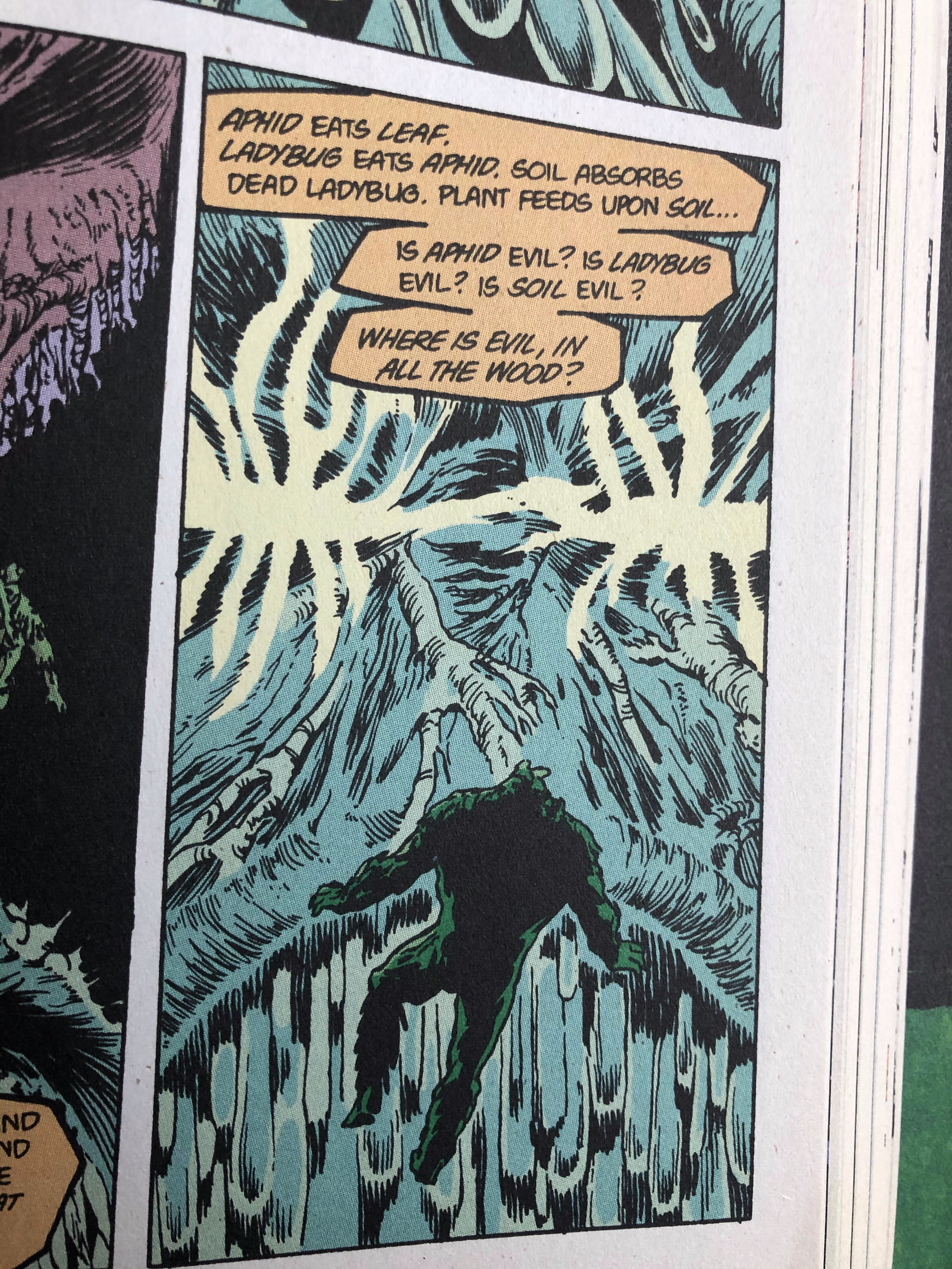

Around when I was leaving my writing job, I became obsessed with the work of comic writer Alan Moore, who argues that art and magic are fundamentally the same thing. Art, he says, is the only human activity that allows you to transport people to other places, other times, other worlds. It's the only way we can enter each other's minds and poke around, it's one of the very few ways we can induce feelings like awe or sadness or joy in our fellow humans.

As magic, of course, writing can also be used as a dark art – it can be used to make people hate, fear, or destroy one another. It can be used to divide and manipulate. Most of us who have chosen lives as writers think of our choices in terms of "career," and how we can "monetize" our talents. This usually means prostituting our skills for advertisers, who want to take this elemental force that we have at our disposal and exploit it to sell cars or beers or pharmaceuticals, or, even worse, as propaganda for cynical politicians or billionaires who want to amass power while destroying the world.

I'm aware that calling writing "magic" or an "elemental force" being cheapened by advertisers and billionaires makes me sound a little self-important, but I'm past the point of caring about that. So much about our culture tells us we're worthless little creatures that can't make a difference or do anything worthwhile, that we're better off leaving the tough work to the "heroes" who are smart enough or powerful enough to make the big boy decisions for us. I'm done with that – I don't think humans are useless. I don't think we're a disease the world needs to be cured of. Thanos wasn't right to destroy half of the life in the universe, and I think that it's crazy that so many people agree with him.

"The landscapes that we exist in, we're going to internalize them, aren't we?" Moore said in an interview with podcaster Will Menaker, "So if you're living in a place that appears to you to be a kind of rat trap, then inevitably, you're going to come to the conclusion that you're probably some kind of rat."

"Whereas if you know anything about the place in which you're living, if you can invest all that brick and mortar with some history, some mythology, whatever, then you can transform the place that you're living in to somewhere out of the Arabian Nights, into a fantastic, magical wonderland, and if you're living in that kind of environment, you might eventually come to the conclusion that you could be a wondrous creature."

Or, as Yoda put it – "Luminous beings are we! Not this crude matter!"

The human mind understands the world through stories, and by grappling with our stories and the ones that surround us, we can start exerting control over the stories we tell ourselves about who we are.

Better Strangers

On a practical level, this means I want to get back to writing what interests me, regardless of how well it fits a "brand" or how it performs in terms of clicks or likes. If it brings me alive, it's worth writing about. So I cast about for a while and finally settled for stealing something from Shakespeare, which has worked well for better artists than me (see: Infinite Jest, The Sound and the Fury, Something Wicked This Way Comes, literally hundreds more). The line comes from As You Like It:

JAQUES. God buy you: let's meet as little as we can.

ORLANDO. I do desire we may be better strangers.

So: the new title is "Better Strangers." I can't claim to have thought too deeply about it, it just hit me as the correct name. And, to be totally transparent, I did not come across it while reading the actual play: I came across it on a coffee mug ("Shakespearean Insults") at Barnes & Noble. I like the sound of it because it could be an insult or an invitation to friendship, and because its initials are "B.S.", which my writing frequently is.

While it will primarily remain my blog, the act of naming it something other than MattHershberger.com means I can call it a "publication" and post the work of my friends, who tend to be creative, thoughtful people.

This site will be fundamentally anti-ad, so if we make any money, it will be either through affiliate links (never Amazon), through selling books or merch, or through Patreon subscriptions. Your support would be appreciated, but I have no plans to quit my day job.

This, in spite of its slick Squarespace layout (Squarespace is less labor intensive than my other options), will hopefully become a small corner of strange on the internet. If it's not for you, that's fine! If you like our version of strange, welcome! Let's become better strangers!

![Graeber’s Bullshit Jobs. [Affiliate link]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5900e73dd2b85756c5b7877a/1571846335028-6X17N0AHTORVG8RT9CY9/bsjobs.jpg)